Is Esa Lindell Overrated, Underrated, or Miscast?

In my opinion, it's none of the above. Allow me to explain...

I was recently watching Game 5 of the 1999 Western Conference Final between the Colorado Avalanche and the Dallas Stars. As a teenager I framed the experience by the sum of its hits and scrums because I was a dumb bloodthirsty young boy who grew up on too much Three Stooges. Now I find myself watching the interplay of systems, routes, and positioning with a more ‘civilized’ eye. I feel like this phenomenon is part of what people are dealing with when we talk about Esa Lindell.

Trying to harmonize old principles with new technology.

People see Lindell, and it triggers the reptilian part of their brain to recall Derian Hatcher and Richard Matvichuk. Make no mistake. Lindell would have been right at home in the dead puck era. But then how might Hatcher and Matvichuk fair in today’s game? That’s impossible to say but watching old video of a different era makes it clear how different a defender’s responsibilities were. Defenders only had to focus on three forwards up in the play at any given time, and they always knew who. Defending the zone was a lock and key situation — as long as you didn’t let them enter the zone easily, routes in the defensive zone would become messy battlegrounds instead of the tic-tac-toe plays they can quickly turn into nowadays.

I assume that was the logic used on Lindell to justify his $5.8 million annual salary. “He shuts the gates.” Except defensive zone hockey is no longer a lock and key situation. It’s now about structure and aggression. I liken it to MMA. Actually, let’s run with his analogy.

Good defensemen are like good fighters.

Think about the NHL’s defensemen of the future: Cale Makar, Charlie McAvoy, Miro Heiskanen, Moritz Seider, and Adam Fox. Fighting, like hockey, is as dynamic a sport there is. Whatever your knowledge (or tolerance) is of prizefighting, they don’t call it the sweet science for nothing. The most talented pugilists have an elite spatial awareness that allows them to turn one decision into multiple options, and those options can turn into an olive branch of solutions (or problems). The best fighters, like the best defensemen, not only switch between offense and defense, but switch between the exertion of control, and ability to reclaim it when lost. Defensemen naturally cover more ice in more minutes so their skills and mindset tend to be more dynamic. They’re puck polymaths. Arguably MMA’s best coach, Greg Jackson, likens mixed martial arts to a series of nodes or game trees.

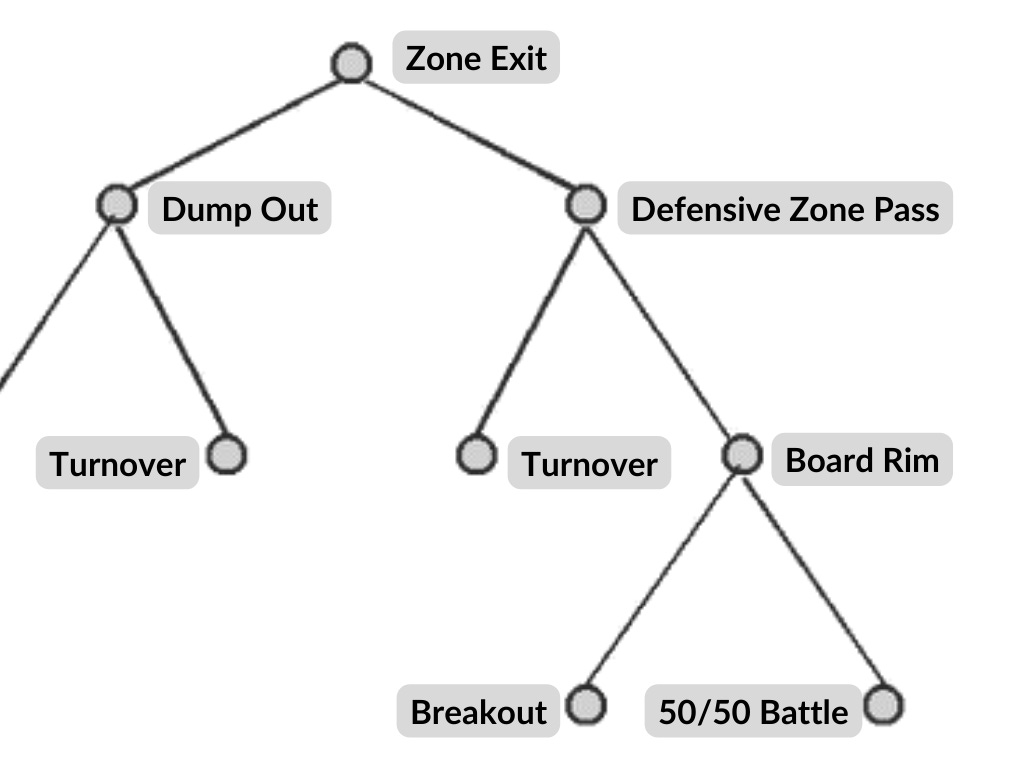

Let’s consider the defensive zone game tree of Lindell’s exits.

Quick note: I want to focus on zone exits for reasons I outlined in my recent article for D Magazine about Heiskanen - they’re one of a defenseman’s most essential pitches (apologies for the rock climbing terminology; I’ve been down a rabbit hole of them for months), and predictive of how they’re able to control the flow of the game. Defenders that exit the zone effectively tend to enter the opponent’s zone effectively too.

If there’s one thing even Lindell’s most ardent fans can agree on it’s that Lindell’s skating is, well…pretty awful. His edgework never improved from his prospect years, and his lack of acceleration leaves him unable to beat defenders one on one when breaking out of the zone (beating the first forechecker is a big part of how Colorado creates so much offense). When exiting the zone, Lindell has two options: a pass, or a dump out. In a dump out, one of two things will happen.

Either it ends in a turnover (I’m not making a distinction here between a direct and an indirect turnover because I don’t think we should - conceding territory to the opponent is conceding territory to the opponent)

Or Dallas regains control.

Lindell will make passes, but when he does, it’s typically a board rim in someone’s direction, which will either end up with Dallas breaking out with possession, or a 50/50 battle. So Lindell’s (very limited) own-zone game tree might look something like this:

These aren’t Lindell’s only options but they are the only options for him. If we were to do a defensive zone game tree for someone like Heiskanen, we’d obviously have a lot more options beyond a dump out or a pass. I know that’s an unfair comparison, but I use it to emphasize that “being good defensively” and being “good in the defensive zone” are not synonymous. Good players tend to be multi-dimensional players, and the same rules apply for forwards; a good shooter won’t just threaten with a wrist shot, but also a snap shot, or slap shot. Lindell is paid because he’s “good in his own zone” but I ask: what part of his own zone? What aspect of defensive zone play are we talking about? There’s more to defending territory than whether you were on the ice when a goal was scored or not. It goes without saying, but how many times have you seen an badly-time icing after an extended shift get exponentially worse?

Nerd alert: Micah Blake McCurdy has some fascinating preliminary research on player off-ice impact i.e. how much does a player affect the next shift? Turns out, there’s a small but tangible residual effect of more shots creating more shots by virtue of gaining more territory, and likewise with defense. This might seem obvious, but it’s interesting to see in mathematical form. Another way of thinking about this concept of territory is - what players are giving the coach the minutes he needs for the usage of others?

Lindell offers none of that modern dynamic. He’s got two moves and neither are conducive to puck control. Originally I starting putting together clips of Lindell in the defensive zone, but it always the same story, so I decided to use the clips of others:

How often have you seen Lindell receive a puck for a quick neutral zone pass…like this?

How often have you seen Lindell win puck races in the defensive corners of the ice…like this?

How often do you see Lindell angle his body and shoulder check for maximum vision to catch the open man in the middle of the ice…like this?

These are all important parts of defensive zone play, yet his reputation is that he’s “good in his own zone.” There’s a solid counterargument to all of this: Lindell’s WAR numbers are not only good, but his defensive metrics from 2019-2022 are elite. Is this a case of analytics illustrating something our eyes are missing?

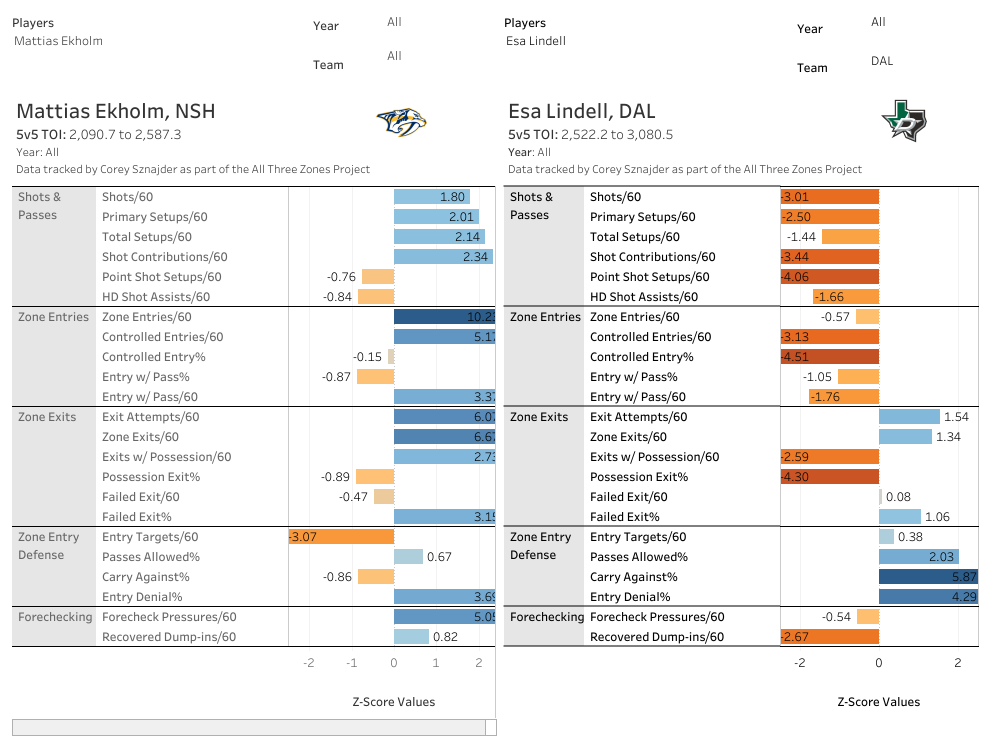

I often think they are but a WAR card is good at evaluating the existence of a player - less so at evaluating the essence of a player. I also don’t think it should be dismissed how atrocious his offense is. That’s not a small thing, and nor are his PK numbers, which you would assume are good because he’s “good in the defensive zone” right? Let’s turn to some other metrics. According to Corey Sznajder’s microdata from 2016 to 2021, Lindell graded out extremely well defending entries, but extremely poor at almost everything else happening in the defensive zone.

Quick note: Why the Mattias Ekholm comparison? I’ve always felt like Ekholm is the player the Stars organization thinks Lindell is.

Is this a tale of two metrics? How do we know which one to trust?

To be fair they’re not necessarily contradicting one another. According to JFresh’s WAR model, he’s good defensively and bad offensively. His tracking data shows the same thing. But his tracking data displays extra layers to defense that aren’t represented in his defensive WAR numbers: namely his inability to win puck battles against the forecheck, recover dump-ins, and exit the zone with possession — I think it also clarifies a contradiction in the ‘Lindell is good defensively’ narrative: if he’s so good in the defensive zone, why is so bad on the PK?

The data isn’t kind. Per Evolving-Hockey, since 2016, Dallas has iced 22 blueliners with at least 20 minutes on the PK. Lindell ranks 15th in shot quality allowed per 60 minutes of play, and 19th in shot attempts allowed.

Let’s also consider the timeline for the data:

WAR data is reflected from 2019-2022 (the Rick Bowness era).

Tracking data is reflected from 2016-2021 (an era that covered Lindy Ruff, Ken Hitchcock, Jim Montgomery, and Bowness).

Does WAR data go back further? In point of fact it does.

I’ve been a skeptic since 2017 when I did a deep dive into the Lindell-Klingberg pairing and found them to be suboptimal because I felt like people were confusing symmetry with chemistry. For me it’s not surprising to see Lindell’s numbers improve under a defense-first coach. We’ve seen a similar phenomenon (in the opposite direction) with John Klingberg, and to a lesser extent, Radek Faksa. Conversely, look at all the offensive players who had banner years under Lindy Ruff. What’s clear to me, and what’s always been clear to me is that Lindell is a defender who is good at the throwback elements of defending but a player who doesn’t have the skills to drive play; moreover, I don’t think we should disregard the connection between offense and defense for the same reason that coaches always lament the lack of defense in a forward’s game. Lindell’s talents don’t interlink with other individuals but he plays a structured game coach’s love. A coach’s love can make all the difference…no matter how bad or suboptimal a player is.

What makes Lindell especially frustrating for me is that we’re not talking about any defenseman: we’re talking about one of the 50 most-expensive blueliners in the NHL. It’s ironic that so many Stars fans complain about Jamie Benn and Tyler Seguin’s cap hit but when it comes to Lindell - “well he’s good at what he does.” In other words, there’s a world in which overpaid players can still be useful? Yes! But the difference is that Benn and Seguin were elite players for a long time. Lindell has never been anywhere close to being elite compared to his peers.

Adding to that, Lindell has been paired with Klingberg since he debuted. Here are Klingberg and Lindell’s career shot and expected goal metrics with and without each other. I’ve included their Rel numbers to highlight what us “haters” have always known: Klingberg will always be Klingberg but who is Lindell without Klingberg?

Clarification for those hazy on “Rel” numbers: Klingberg’s 2.12 career CF percentage relative to Dallas means the Stars were a full two+ percentage points better with Klingberg on the ice than without him. Dallas’ shot attempt percentage with Klingberg on the roster is 50.55 percent since 2014. Without him, Dallas’ CF drops to 48.43. Conversely, Dallas’ CF increases to 53.39 percent…without Lindell. Their xGF percentage increases to 54.36 (from 51.58 percent) percent…without Lindell. While I don’t believe shot metrics are good way to analyze defenders, that’s a massive swing.

Honestly, I thought I’d have more positive things to say about Lindell. I thought I’d eventually settle on one of underrated, overrated, or miscast. But I can’t help but imagine a parallel universe where Dallas keeps Alex Goligoski on that first paring with Klingberg. They were good together. In both seasons from 2014 to 2016, they were a +13 and +14 in even strength shot attempt differential. With Lindell, the top pair was a minus in every season except for the year with Hitchcock and the first full season under Bowness (where they were a +1). In that universe Lindell is a solid wingman next to Jason Demers, or Stephen Johns, but he is not one of the 50 most expensive blueliners. Does Klingberg even leave in that alternate universe, even knowing how badly his agent screwed the pooch?

Not all analysis needs to abide by some nebulous “two sides” rule. Lindell is good at some defensive things, bad at other defensive things, bad offensively, doesn’t drive play, drags down the team’s ability to create offense, has clearly had Klingberg pull him up by his bootstraps, yet somehow takes up 7 percent of the team’s increasingly squeezed cap. What other conclusion am I supposed to draw about a player’s value? He’s overpaid and overvalued: full stop.

BUT…that doesn’t mean there aren’t caveats, nor does it mean I have nothing positive to say about him. Sometimes the pendulum swings too far the other way. While the demand for rovers, and puck moving defenders is still relatively high, I think we’re finally starting to see a renewed appreciation for modern shutdown defenders as the stock of players like Shayne Gostisbehere and Tyson Barrie fall. Recall that Heiskanen and Seider were expected to be drafted much lower because they they had questionable “offensive ceilings.” Ottawa’s Jake Sanderson is another great example who, although drafted higher than expected, seems primed to make a difference despite not projecting to be a big point producer. Hell I love Artyom Grushnikov despite the fact that he scored 12 points last year for the OHL’s Hamilton Bulldogs. Why? Because he plays strong in the defensive zone. The difference between Grushnikov, Lian Bichsel (who will be even better), and Lindell is that the former two players can turn defense into control; can scramble out of the defensive zone in ways that shorten the ice so that good defense can turn into offense; defenders - like Ekholm - who prove that you can have a complex game tree despite a limited skillset. Lindell offers a dynamic that almost feels archaic by comparison. He’s not obsolete. He’s just adequate.

Ok so technically I didn’t say anything positive in that last paragraph about Lindell so let me try again. I do think just as we’ve seen player performance fluctuate under different coaches and systems, it’s possible Pete DeBoer might unlock some of the offensive potential Lindell was originally drafted for. It’s important to remember that it wasn’t just offensive defenders like Burns and Theodore he had get more involved in the play. It was also players like Marc-Edouard Vlasic and Nick Holden that DeBoer had shooting more. Lindell has a really good wrist shot, and powers through single lanes with momentum and confidence. With the lack of defenders able to fill in an offensive role and the need for players like Lindell to step up, could this be another perfect marriage?

I hope so. I just hope Bichsel and Grushnikov are ready sooner rather than later. At least one of them might be able to one day justify $5.8 million against the annual cap for good defense and bad offense rather than some good defense, and bad offense.