This will be part one in a three-part series. Next week we’ll discuss the defense, and the week after goaltending/special teams. From June 7-24 I’ll be writing draft profiles as well. Like I said: this place won’t skip a beat. Kind of like with our playoff previews, the broad strokes will be for unpaid subscribers, and we’ll get into the weeds for the sickos (paid) in the second half.

Are we all sobered up? Good.

The Dallas Stars were one of the league’s top offenses in the regular season. 294 goals put them behind only Toronto (298), and Colorado (302). Depth was the word of the day. Led by Roope Hintz and Jason Robertson, the emerging core of Wyatt Johnston and Logan Stankoven ignited victory green waves of attack that was already buoyed by veterans who remained productive despite presumably being past their Sell-By date. It looked like the perfect recipe.

Unfortunately as good as the recipe looked, it lacked flavor in the end. Dallas went from being an elite offensive team to a middling one once the league shifted to a 16-team format. In the postseason, Robertson and Johnston led the way with 16 points in 19 games. They were followed by Jamie Benn (15) and Tyler Seguin (13). On the surface, that seems good. Their two best forwards were highly productive, while the grumpy old men provided ample support. So what happened?

We’ll start with the obvious. Three key pieces went missing: Roope Hintz, Joe Pavelski, and Matt Duchene. This was especially true in the final series. The only players who scored goals versus the Oilers besides Johnston and Robertson were Mason Marchment (2), Tyler Seguin (2), and Jamie Benn (1). Meanwhile, Edmonton had six forwards who scored a goal beyond their top two players in Connor McDavid and Leon Draisaitl: Zach Hymen, Ryan Nugent-Hopkins, Adam Henrique, Connor Brown, Mattias Janmark, and Ryan McLeod.

So not only did Edmonton win the superstar battle, but so did their depth. Now let’s move to the not-so-obvious. Should we have seen this coming? Yes, actually.

Was Dallas’ depth a mirage all along?

This is where we’ll dig into some analytics. Below is the true rating per sG of Dallas’ forwards during the regular season.

Not sure what this chart means and need a quick and dirty explainer? I’ve got you covered! Click here to learn more from a man who knows less.

A digression: why sG is more than just an “analytic”

I’d advise clicking the link even if you’re only a little curious. Hell, even if you have a problem with math or are the classic Eye Test type sick to death of all this Moneyball nonsense. I think I’ve done my level best to make it as easy-to-read for the layfan as possible while respecting the complexity of what Micah’s model is aiming to do. I’ve skipped as much talking about the model portion of sG as possible in favor of getting to the heart of what question it’s trying to ask, and what that answer means for how we evaluate players.

One reason why I want to emphasize sG, and why you should have some loose knowledge of it, is that I consider it highly relevant to the current discussion. Even if sG is not your hockey bible, you should have an appreciation for what it’s trying to tell you because I think it’s a key piece in unpacking what went wrong. After all, don’t you want to know why Dallas’ depth disappeared?

Back to your regularly scheduled programming

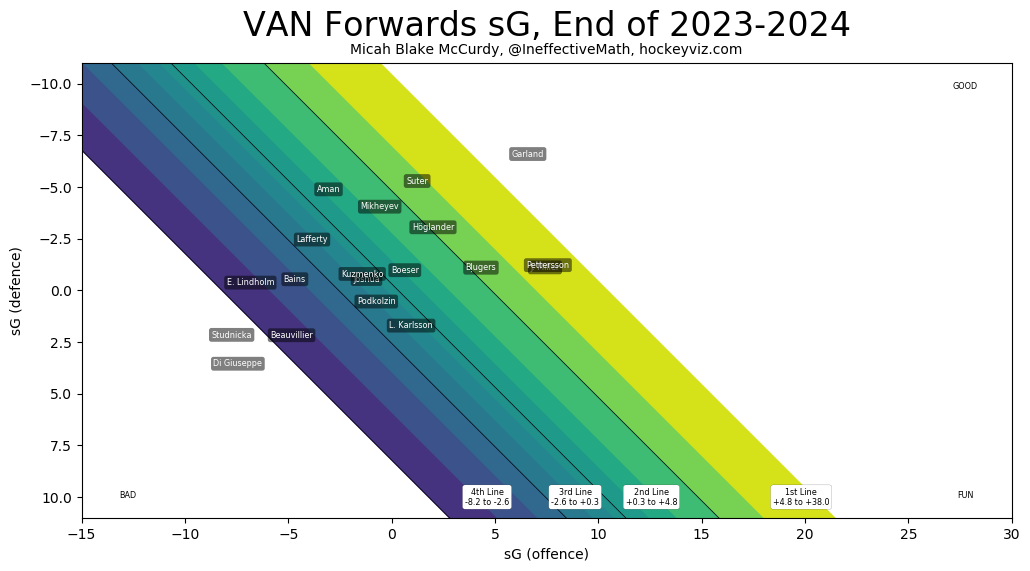

Looking back at Micah’s chart above for Dallas’ forwards, it’s easy to see why. I realize this will be a major point of contention for some people. And I don’t want to christen a mathematical model as our only source of reference or understanding here, but the numbers clue us to an uncomfortable truth: players like Duchene, Pavelski, and Seguin picked up a lot of points in the regular season, but it wasn’t sustainable production. They were net negatives in terms of shift to shift impact, with Pavelski and Duchene in particular profiling like fourth liners. In fact, Dallas kind of reminded me of another team that was a little inflated all year: Vancouver.

Same thing. Notice how just like Dallas players with a low intrinsic rating played big minutes, so did Vancouver, with players like Elias Lindholm too high on the depth chart, and stars like Brock Boeser performing below expectation (box score be damned).

I understand that this thesis won’t work for people who don’t buy what sG is selling. After all, Pavelski and Duchene are not fourth liners. “Fourth liners” don’t score 60+ points. However, sG is neither a box score, nor a scouting report. In many ways, it’s a shift report, or rather, a system of shift reporting. That’s the point of these: we’re trying to resolve a contradiction. How did those 60 point players look so bad in the playoffs? There’s your answer: not every 60-point player is a top six forward. Call this the Jonathan Cheechoo Principle, if you will. Timelines tend to bias our understanding. After all, a productive regular season should mean a productive postseason. This is where I think it’s important to look at production and performance on a continuum rather artificially-separated seasons defined by only goals and assists. Otherwise, we can end up with illusions, and illusions can come in many different forms: Alex Chiasson, Devin Shore, etc.

Getting back to the broad point, Dallas only had had seven players who profiled like a top six forward per sG. How many did Edmonton have? Surprise, surprise: same amount.

Re-thinking Dallas’ Trios

Edmonton beat Dallas’ depth not because they had better depth per se (although in a vacuum they still won the fight) but because Dallas was never really built on depth. They just had a lot of guys with a lot of points. I would argue there’s a difference, and there’s no better proof of the other end of that spectrum than the Florida Panthers.

Just because Micah’s model has a word like “synthetic” in the title doesn’t mean we’re dealing with something abstract. What did we see from Pavelski and Duchene from shift to shift? A lot, none of it positive. Pavelski couldn’t connect a single pass, and worse, his passes were consistently on the tape of the opponents. Duchene and Pavelski were Dallas’ two worst players in giveaways per hour at even strength. Pavelski was a -5 in faceoff differential. Neither man could draw a penalty. Pavelski at least had an excuse, whereas Duchene kept making the same mistake, overhandling the puck and looking to make that extra move in spaces that weren’t there like they were in the regular season.

sG may be not be able to ‘watch the games’ but it identifies each event as significant. There’s nothing mercurial about two players consistently losing Dallas territory, squandering pressure, making Dallas more likely to defend in their own zone, and only being able to make a difference when they get a clean shot. That kind of thing adds up, wouldn’t you say?

Nowhere is this more evident than when we evaluate players in their natural habitat: as teammates. To drive this point home even further, here were Dallas’ top four groups in expected goals (blue bars), actual goals per game (red bars), and the league average for all forward groups (bottom two) with at least 200 minutes together. Pay attention to the blue bar at the bottom.

Except for the Benn-Johnston-Stankoven line, they were all below league average in terms of shot quality generated per hour. That’s significant. That’s one forward line that could sustainably threaten the opposing defense. In the playoffs, that’s exactly what it looked like.

There are other discussions to be had here, in part because Dallas may consider bringing back someone like Duchene. Is that a good idea? Is there a way to make it work? Is it enough to find a forward who can impact possession from shift to shift but who has a hard cap on how often they can score, like say, an Evan Rodrigues? That’s what we’ll try to answer in the paid section.

But first, let’s look at Florida’s forward group. I want to strengthen this argument a bit more and the Panthers are thankfully a helping touchstone towards understanding this. They’re the antithesis to Dallas in many ways in that their forwards don’t score a lot, but boy do they drive play.