The Dallas Stars Own the Faceoff Circle, But How Much Does it Matter?

More faceoff wins is a good thing, right? Or is it just...a thing?

The Dallas Stars have an interesting lineup. Most of their forwards can take faceoffs, either owed to being natural centers forced to play wing (like Tyler Seguin), or being wingers forced to play center (previously Max Domi). If Dallas’ fourth line were Sam Steel with Radek Faksa and Ty Dellandrea, 75 percent of their forward lineup would consist of dual-role forwards. Kind of cool, right? But what exactly is the bottom line?

I don’t know. For the nerdonauts, faceoffs have always been a point of contention. There are around 60 faceoffs per game, and still no one has any idea what they mean statistically. Conversely, with the way commentators gas up the importance of faceoffs, you’d expect more goal scoring with so many faceoffs. Except hockey is a low-scoring sport comparatively speaking.

There’s a lot to unpack about faceoffs for reasons that have nothing to do with analytics. It’s really about language. This is the real reason why I lean so heavily on “analytics”. Not because I want to know if the math checks out but because I want to use words that mean things. Why talk about good players versus bad players when you can talk about varying degrees of strong possession players versus weak ones, or rush attackers versus cyclers, players that excel breaking out of the zone versus those that excel by entering their opponents, etc.

Same thing with faceoffs. They’re complicated for what they don’t represent more than what they do. Dallas is a really good team (top three according to Dom’s Net Rating for the upcoming season) that’s good at them. Correlation, causation, or something else?

Why Faceoffs Don’t Matter: But With An Important Caveat

If we simply ask ‘do faceoffs matter?’ then we’re asking the wrong question. It’s a little like asking ‘did Jamie Benn’s zone entry on his second shift in the third period matter?’ You certainly want to see Benn enter the opponent’s zone. But what did he do with it? Did Dallas generate a shot with it? Did Benn turn the puck over? What happened as a direct result?

Thinking about the broad implications is what led to Gabriel Desjardins’ doing more comprehensive study on a faceoff’s impact long term. What he found is that 100 extra faceoff wins would net teams an extra 2.45 goals.

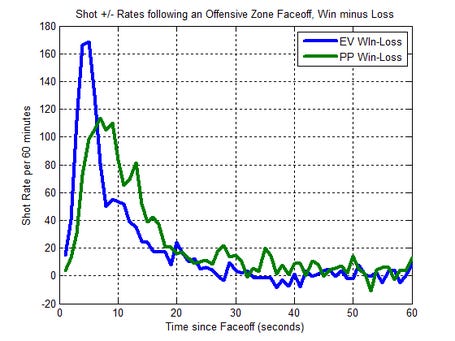

Having extra faceoffs doesn’t mean much, so what about those 10 seconds? Craig Tabita’s further study on net shots following a faceoff found that shot volume within the first 10 seconds eventually evened out. From 2009 to 2015, one goal was scored within 10 seconds of an EV faceoff once every four games. So yea: faceoffs don’t matter in the long run. At least if we’re asking a vague question like “do faceoffs matter?”

This always made sense to me upon reflection. Why would one event, which doesn’t even guarantee a shot, let alone a goal, be that big of a deal? I understand the impulse. We’re talking about an event that literally shifts control from one team to the other. On the other hand, it’s just one event. Why should faceoffs matter more than goals, entries, exits, the forecheck, or the rush? If the guy winning the faceoff has poor puck control and his team bleeds chances when he’s on the ice, then WGAF?

So far, this still doesn’t explain what’s going on with Dallas. If faceoffs don’t matter, then why is Dallas so good? They were the best faceoff team in the NHL, and one of the best teams in general. They had three players over 56 percent on the faceoff dot (Benn, Luke Glendening, and Radek Faksa), and another three at 52 percent (Seguin, Joe Pavelski, and Roope Hintz).

Also, the top five faceoff teams this year were as follows:

Dallas Stars

Boston Bruins

Los Angeles Kings

Toronto Maple Leafs

Carolina Hurricanes

Why Faceoffs DO Matter: But With An Important Caveat

But perhaps we’ve been asking the wrong question. Let’s change it up. Now let’s ask this about faceoffs: can a team directly benefit from winning them more frequently? In point of fact, yes they can. The Sharks had a brief run in 2011 where, according to research from Michael Schuckers, San Jose managed to add six goals from their faceoff prowess. But what if we further amended the original question to include clean faceoff wins, which current research suggests makes an impact previous studies have failed to account for? Again, now we’re getting somewhere.

That’s what Nick Czuzoj-Schulman’s 2019 study focused on. Defining a clean faceoff win as a faceoff win immediately transitioning the puck directly from the center to their linemate, he adds:

Sportlogiq’s analysis found that a clean win in the offensive zone led to a shot on goal or scoring chance 38.6 percent of the time, versus 30.3 percent for non-clean wins. But not all clean wins are created equal. Clean wins directed back and to the inside of the faceoff circle led to shot events 43.6 percent of the time, compared with 32.1 percent for non-clean wins. Clean wins were also directed to a teammate’s stick 25 percent faster than non-clean wins.

It’s not a lot — is there a correlation between clean faceoffs wins and single-game performance? What about clean faceoff wins and their connection to player performance? — but it’s a working definition towards a better understanding of the degree to which they affect play. So what’s the lesson here?

Nothing you don’t already know: every advantage, no matter how small, is a gift in a sport as chaotic as hockey.

The other thing I’d add in favor of faceoffs and their importance is that the set plays that occur from faceoff wins tend to be more quickly executed. Players perfect routes that flow from them, revealing plays that a team has practiced with extreme precision. It’s one of the rare glimpses into each panel of what a team drew up. Faceoff wins are just fun. Whatever they mean long term, when they happen — shit gets real.

When Seeing is Believing Without Proving

Here are the top 20 faceoff teams since 2007 and their points percentage (in red). Notice the two Dallas squads? (Forgive the incorrect duplication of years)

If faceoffs were so essential, then why did one squad dominate them and crap the bad offensively while the other dominated them left earth offensively? Could it be because faceoffs were only peripheral to what made one attack efficient?

Only four of the last 11 Stanley Cup winners had a faceoff win percentage over fifty percent. Wyatt Johnston was 43 percent on the dots. Remember that top five list I just gave you of the best faceoff teams last year? In sixth place was the Chicago Blackhawks. It’s obviously better to win faceoffs than to lose them, but advantages can take the shape in many different forms.

In Dallas’ case what we’re seeing is a great team that happens to be great on the dots too. Their faceoff prowess is merely incidental. It’s not what makes them special. What makes them special is their top line, Miro Heiskanen, aging veterans finding their second wind, Jake Oettinger, Pete DeBoer’s system, and Jim Nill’s recent draft run. (Although the scouting department’s record on defensemen beyond the first round is starting to ruffle my feathers.)

But there’s a broader point to make within the discussion, and it’s about human psychology.

Faceoffs are similar to the phenomenon that sets us up to incorrectly think homicide is more dangerous than diabetes, that tornadoes are more dangerous than lightning, or that car accidents are more dangerous than abdominal cancer. We overestimate their incidence because the ease with which we access the information is mistaken for its frequency.

Faceoff wins aren’t frequent. Dallas’ balanced attack, however, is. Of course I’ll change my tune during a faceoff win in the dying seconds of a Stanley Cup Final. But I’d be missing the point. Nobody wins or loses based on one event. They win or lose based on the process that earned them their place at the table to begin with.

So this sent me down a random, looking at stats wormhole.

Last season, for playoffs and regular season combined, the Stars won 56 percent of faceoffs in victories. That's 58 percent in defensive zone, 56 in the neutral zone, and 55 percent in the attacking zone.

In losses, the Stars won 53 percent of faceoffs. They were 55 percent in the defensive zone, 52 percent in neutral, and 52 percent in attacking zone.

This is where we get anecdotal and how, and why coaches would use this data to motivate a team. Faceoffs are a reflection of effort, when you give a little bit more effort, 3 percent more in the faceoff circle, we win games. When we get less effort we lose.

In the playoffs only, the Stars in victories, they won 57 percent of the draws overall. 58 percent in the defensive zone, 53 percent in neutral, and 59 percent in the attacking zone.

In playoff losses, they were 53 percent total in the circle. 53 percent in the defensive zone, 48 percent in neutral, and 56 percent in the attacking zone.

Again anecdotal, but from a coaching message standpoint, 4 percent extra effort in the circle is the difference between winning and losing in the playoffs. That's a message you can package and deliver when asking for a bit more from tired lineup in the locker room.

To finish off my rambling, faceoffs matter for Dallas not because they win or lose games necessarily, but faceoff percentage is a pretty good reflection of whether Dallas played it's desired game in a a respective evening. It's not all about effort, but it was one of the few stats that we can anecdotally connect to it that isn't impacted by outside noise.

Hope this all makes sense.

Great article about the nuance of faceoffs… two points, obviously possession is preferable, so does a possession advantage derived from faceoff wins show as a determining factor in wins?

Secondly, and this idea throws the ability to analyze faceoffs out the window… I once heard it said that faceoff win % isn’t important, what’s important is winning KEY faceoffs… ie Power Play offensive zone, PK in defensive zone… and I think some guys hold back their faceoff “trick” until those key moments… like holding back your super curve ball for strikeouts!